Bloomberg’s 7 Powers & Why the Terminal dominates financial markets

The definitive guide to why no one has killed the Bloomberg Terminal, yet.

Bloomberg Killers

Since the early 90s, Bloomberg has always been on somebody’s kill list. Oddly, the list of potential Bloomberg Killers has grown every few years and has never crowned a king. Many on the list instead ended up as road kill to Bloomberg’s growth story. Why has this been the case, and why does history keep repeating itself? And despite the track record, why are attempts still being made to topple Bloomberg?

As someone who has spent many years in the industry, starting with this note, I aim to put together a series of articles that will serve as the first definitive guide on Bloomberg, its peers, new entrants and challengers alike. Using company profiles, business breakdowns, founder stories, and market commentary, I hope to uncover and explain new opportunities and share learnings from successful company builders. In doing so, I wish to help the brave souls wanting to disrupt Bloomberg demystify the fog of war and understand the enemy and the battlefield better. I’d consider this pursuit successful if it attracts more innovators and investors into this space, which has long received little public attention.

To succeed with this grandiose mission, we must first develop the right frame of reference on Bloomberg. What is the closest comparable to Bloomberg that best explains its breadth, depth & complexity? A simple analogy might be helpful to start with.

What does Bloomberg do?

Imagine that your ISP (connectivity), browser (interface), OS (orchestration), app store (functionality), search engine (directory), social network (chat), and media houses (news & data) were all run and owned by a single company. That would require the company to be AT&T, Apple, Google, Facebook & News+Fox Corp all rolled into one.

Now, transpose this idea onto the world of finance, and you'll begin to grasp what Bloomberg does. At its core is the Bloomberg Terminal, a unified interface that serves as the gateway to a vast financial ecosystem. This interface is powered by a complex orchestration layer, managing and processing enormous amounts of real-time data.

Through this platform, Bloomberg provides connectivity to a global financial network and functionality across tools for analysis, trading, and risk management. Users can access the latest news and company financial data in seconds through a powerful directory that has indexed it all. The chat function knits together a global network of finance professionals for real-time communication.

Bloomberg's comprehensive integration of these elements has established it as the operating system that powers modern finance. Not the only one, but arguably the first!

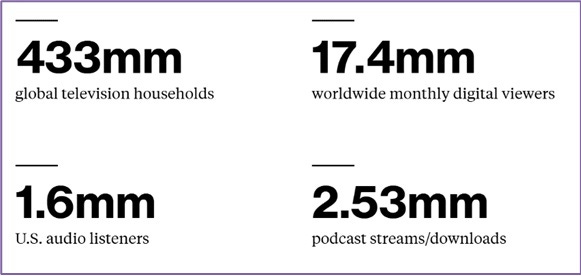

The breadth and depth of Bloomberg's capabilities, coverage, and scope are beyond the scope of this article. It is shockingly immense, and figures would surprise even long-term users, most of whom never see the entire offering. If the above analogy wasn't enough, here are some numbers as a teaser,

'the terminal processes an average of more than 300 billion bits of financial information and sends about 1.4 billion messages and 30 million "Instant Bloomberg" chat messages that ricochet around the world' (the FT).

Hopefully, you already have a general sense of what Bloomberg does, what the Terminal is capable of, and how users swear by it. If not here are some company videos to get you broadly started. If that was too much, I’ll break it down step by step below.

Why is Bloomberg so successful?

While this can be structured in many ways, I've used my favorite framework from my favorite podcast - Hamilton Helmer's Seven Powers from Acquired. If you haven't come across this framework before, I recommend Quartr's take for a quick read, and Abi Tunggal's longer deep dive.

First, some quick caveats on my writing:

Adjectives, comparison and descriptions are mostly directional and relative, not literal and absolute.

This article aims to broadly explain the many factors that have led to Bloomberg's success. Some of these success factors may also be true of its peers. These success factors are however not a verdict on the Terminal's future.

Key points may be reiterated from different perspectives to enhance understanding.

While I've aimed for objectivity, my admiration for Bloomberg's achievements may color the analysis. I welcome critical perspectives.

As an industry insider (though not Bloomberg-affiliated), this represents my best understanding, and may not be exhaustive.

For simplicity, "The Terminal" refers to Bloomberg's evolving interface to access the world’s financial data, from the early standalone hardware to today's omni-channel software and dedicated keyboards. The tight coupling of hardware and software warrants a further study, but sadly product-level distinctions are beyond this (first) article's scope.

Now that we've laid the groundwork and set expectations, let's dive into the analysis. We'll explore each of the Seven Powers in the order I believe they emerged for Bloomberg, providing a chronological perspective on the company's evolving competitive advantages.

1. Cornered resource

(preferential or exclusive access to a limited resource)

While data is one of the various value layers in which Bloomberg operates, it is the golden goose. The Terminal, a firehose of information, is a modern marvel that feeds on multiple data resources that Bloomberg has cornered. Let’s break them down one at a time.

a. Bonds – proprietary data on pricing, liquidity, and trades

The first market Bloomberg cornered was bonds, both by chance and design.

By chance as the company launched in 1981 just as the global bond markets were experiencing explosive growth. The debt boom saw the Eurodollar bond market grow 67x, secondary trading of treasuries grow 10x, and junk bonds grow 19x in different 10 year windows surrounding 1981.

By design as Bloomberg responded with industry-leading real-time graphing and analytics tools to interpret the increasingly complex market that won its first client and opened the floodgates for the rest. They leaned in heavily to the niche, soon establishing themselves as the primary (and often the only) source of pricing, liquidity, and execution for various categories of bonds. They created a network of tools (ALLQ, DEBT, YAS) and connectivity for a heavily OTC asset class. In a winner-take-all market (due to network effects), a trader would struggle to trade, discover price or uncover inventory without a Terminal. Chat introduced in the early 2000s was a well-timed adoption hook (discussed under Network Effects) as the market shifted from voice to chat-based execution.

A stranglehold on bonds, a significantly broader asset class than stocks, made Bloomberg indispensable to the fabric of the financial markets. To understand the difference in scale, consider a 2021 FT article that puts the number of corporate bonds in just the US alone as more than ten times the number of all stocks listed globally. That comparison does not include government, munis and asset-backed securities, which number in the millions. Bloomberg learnt early how to grapple with enormous breadth and depth of data and the importance of this asset class.

Winning in pricing, liquidity, and execution layers also provided a massive data exhaust from all the generated trade, quote, and orderbook information. This dataset formed the backbone for monetized usecases - yield and price analytics, sensitivity testing, indices formation, and benchmarking - with zero (or minimal) marginal cost to Bloomberg. The proprietary data history for much of the asset class remains a coveted resource.

This dominance is beginning to change with new competition riding the electronification wave of bond trading. However, Bloomberg has responded with new trade execution services (BOLT, BRIDGE) and has arrested market share declines to Marketaxess & Tradeweb.

b. FX – proprietary data on pricing, liquidity, and trades

While not as dominant as in bonds, Bloomberg was still part of the oligopoly in the FX markets ‘00s and ‘10s, with a meaningful share of liquidity and execution. As the largest traded asset class by volume ($7 trillion a day), FX was a key stronghold to build.

FX is primarily an interbank market, with the top 10 banks managing 66% of the volume as of 2022, unchanged from 2016. The Terminal just offered an independent venue for these banks to come together to transact, offering electronic connectivity between participants as well has offering the GUI to trade. Unlike bonds, they weren’t the first to market, leaving competitors to take the top 2 spots.

Nevertheless, the data exhaust is significant and provided more opportunities to strengthen the moat. While not a strictly cornered resource anymore – strong competition from FXAll, FXConnect, EBS, 360T – it continues to be a winning offering.

c. News – an in-house desk reporting on market-moving news

One of the masterstrokes in business history and competitive positioning was the creation of Bloomberg News. News drives prices, and price movement drives engagement. Not only did the Terminal provide users with real-time pricing, but it also provided the stories that affected it.

A dedicated team of editors, journalists, and reporters working only for Bloomberg were tasked with generating proprietary financial content. An in-house team could better optimize for speed, accuracy, and brevity to convey headlines to capital allocators. The existing low latency infra provided the rails and the Terminal with the distribution needed to scale fast.

In a world where a news report received a few seconds late could mean millions in losses, Bloomberg News (along with Reuters) became the go-to for traders and money managers. More subscriptions led to more news editors and reporters, which led to broader, deeper, and faster coverage, which attracted more subscribers. The flywheel never looked back growing to a 2700 reporter team across 70 countries producing a wide range of content.

To further the moat, Bloomberg increased the co-dependence of the Terminal with News. Bloomberg News is distributed through the Terminal first – in real time. Any user that believes that Bloomberg will even occasionally (i.e. more than once a year) break certain market-moving headlines first must necessarily have the Terminal if the timely receipt of the news can protect against a greater than $30,000 loss (the cost of the Terminal).

(Most headlines) are “flashes” produced by human specialists manning the company’s “speed desk.” The fastest can generate a headline from an incoming release in “a shade under 4.5 seconds,”

The stories behind the creation and growth of Bloomberg News are an excellent read in its own right, a testament to what happens when visionary business acumen meets relentless execution.

d. Fundamental data – company financials disclosed quarterly and in annual reports

While some exchanges & regulators have normalized financial reporting by listed companies in the last 15 years, company financial reporting before that varied by formats, nomenclatures, and accounting standards. They had to be manually collected, scrubbed, standardized and aggregated. A tedious task that we’ll further look at in Process Power.

Painstakingly doing this for years eventually led to a proprietary database of financials for 85,000 companies across 115 countries with a history of up to 40 years. The database includes all the numerical info from balance sheets, income statements, cash flows, shareholders and share counts, buybacks and dividends, debt profiles, and many more. A set of processes on top of this raw data then derives financial ratios and benchmarks.

After real-time price and news data, this is the most valued dataset in the market. Demand has exploded with the rise of research funds, portfolio managers & quants. Every money manager needs this to run their valuation models, decipher earnings and profitability, and understand where company cashflows are being directed. It answers questions like - are insiders buying, how much debt is due next year, are interest payments rising, how much was spent in R&D, and so on. Every piece of info in this dataset can be a source of alpha in the right hands.

Surprisingly, few companies remain the ‘true/original’ source of long-term historical data, and the market has long been captive to them. Bloomberg now enjoys the fruit of labor done decades ago.

e. Analytics tools – to analyze individual securities and instruments

Financial data is complex and voluminous. Interpreting and studying it requires sophisticated tools that need advanced degrees to understand. Bloomberg’s myriad proprietary tools and calculators span modelling, scenario testing, risk analysis, back testing, etc., further separated by asset, sub-asset, and sub-sub-asset class. The divergent nature and properties of different asset classes necessitate separate tooling, analysis frameworks and methodologies for assessment. Conversely, given the niche focus, each tool isn’t widely applicable across the user base. Unsurprisingly, third-party vendors of niche analytical tools tend to be much smaller due to the limited addressable user base.

Without Bloomberg, a large client that operates across asset classes and needs a broad range of analytical tools has to sieve through a voluminous, fragmented industry of small providers and stitch together their offerings to various user groups. Each comes with costs and overheads like testing, repackaging, customization, deployment, and issue resolution. Most clients don’t want to deal with a battery of vendors for niche requirements. Banks pay for convenience, speed and friction-free access to tools. Few vendors have offered a sum of parts greater than Bloomberg’s whole – an aggregated provider that provides across the spectrum of needs.

f. Proprietary/exclusive data – in adjacent or alternative asset classes

Beyond bonds & FX, Bloomberg has built proprietary databases in alternative classes – e.g. energy, commodities, carbon, and ESG. This has been achieved through strategic acquisitions over time – Second Measure (consumer data), New Energy Finance, Netbox (social media surveillance)- and through exclusive distribution agreements with various third-party data vendors that track niche and esoteric fields – container ship tracking, evictions and foreclosures, geopolitical risk metrics, regional internet usage, patent data, night lights radiance.

Hedge funds, by definition, have to find alpha, and so their thirst for new kinds of alternative investment data is insatiable. As public and restricted data becomes over-mined and saturated, the market is constantly looking for alternative datasets.

While Bloomberg has been silent on its data acquisition strategy, the arsenal of proprietary data under the hood will continue to grow and become available at an increasing premium.

g. Data Licensing - a rigid framework for maximum control on their data

Bloomberg’s data licensing framework dictates how its data can be used, reused, modified, redistributed and further derived. The framework ensures they have complete line-of-sight of their data as it passes through different gateways, entities and products in the value chain. This allows them to monetize across multiple nodes in the value chain, often ensuring nodes two or three times removed are correctly taxed for their data usage.

An example of how monetization works for Bloomberg through costs incurred at different stages/nodes for a large banking customer

internal users – cost of Terminals for human use,

internal systems – cost of data distributed for machine use, i.e. monitoring systems, trading algorithms, reconciliation and settlement back ends,

customers and clients – cost of data redistributed for external human use i.e. for client statements and customer portals

supporting vendors – cost of data licenses for third-party vendors building ancillary or core products for the same customers

That last bit 4. requires a footnote to understand the sneaky double-charging practices the industry has gotten away with1. Most B2B fintechs building enterprise solutions that rely on market data have probably had their pockets picked as they were unaware of how licensing works. Thankfully, new forms of tri-party agreements are slowly becoming more common to avoid this issue. Reach out in the comments if you need help.

To appreciate how restrictive data licensing can be, consider the prose in their TOS. Instructive, intriguing and intense –

‘… you may not copy, reproduce, recompile, decompile, disassemble, reverse engineer, distribute, publish, display, perform, modify, upload to, create derivative works from, transmit, transfer, sell, license, upload, edit post, frame, link, or in any way exploit any part of the Service…’

&

‘unauthorized use, copying, reproduction, modification, publication, republication, uploading, framing, downloading, posting, transmitting, distributing, duplicating or any other misuse of any of the service is strictly prohibited’

&

‘You agree not to use, transfer, distribute, or dispose of any information contained in the Service in any manner that could compete with the business of Bloomberg or any of its suppliers.’

Not the most encouraging words to read if you are trying to innovate with financial market data. That last bit in bold is intentionally vague and limiting, given how diverse and expansive their products and services are. If and when a new entrant seems to be approaching critical mass, Bloomberg has this in the back pocket to manage that threat.

2. Process power

(benefits that cannot be replicated without due investments in time, capital & people)

a. Real-time network infrastructure

Organic and inorganic investments made over decades have built a (near) unbreakable, proprietary, high-bandwidth, low-latency network capable of moving real-time price information on tens of thousands of stocks across hundreds of exchanges at the millisecond quantum to 350,000+ users. This was set up pre-cloud and pre-SaaS tooling, with dedicated hardware, software, and programming languages. Millions, if not billions of dollars and person-hours were invested. Now, billions, if not trillions of dollars ride on the speed, accuracy & uptime of this network. Let that sink in.

The real-time network is both the nervous and circulatory system of the financial markets. Real-time price data is what traders have their eyes glued to across multiple screens. It’s what everyone sees on CNBC, that price ticker scrolling at the bottom of the screen. It’s what drives every stock market frenzy and every stock market crash. Heck, it’s what’s keeping Jim Cramer alive. Real-time data makes financial markets exciting. Without it, the world would be, well probably more peaceful.

A vast, complex engineering marvel (the Ticker Plant, covered later) sits behind the Terminal to ingest, process, and distribute such a high throughput of data at a global scale. It needs 24x7 uptime and has faced fewer outages than AWS. Bloomberg has been perfecting it for 40 years. This advantage can’t be scaled overnight.

b. Collection, aggregation & standardization

The competitive edge gained by building low latency networks for real-time data does not translate to an edge for company financial or instrument data. Gaining an edge here required robust collection, aggregation & standardization mechanisms and flexible, concorded systems for storage and distribution.

Data collection is a mammoth task, spanning various asset classes and data types. To understand the disparate range of requirements, consider the variation in the following asset classes:

Exchange-traded instruments – as observed in Company Financials under Cornered Resources, there are differing reporting requirements, cycles, disclosures, and formats across 100+ exchanges and respective regulatory policies, differing KPIs and metrics to be tracked per industry

OTC bonds, funds, derivatives – separate collection mechanisms are needed to plug into the origination process of each instrument across different originators (commercial and investment banks, asset managers, fund houses, clearing houses, registrars, etc.), followed by up-to-date maintenance of all capital flow, events, and outcomes

Non-instrument data – economic, societal, demographic, geographic, industry/sector specific datasets must be collected across countries, governments, industry bodies, and trade associations.

The above skims the complexity in just the collection phase. The data must then be cleaned, formatted, calibrated, standardized and re-ingested into type-specific databases. Standardized schema, taxonomy and metadata must be defined along with processes and tools to ensure accuracy, concordance and timeliness. One can appreciate the high degree of process variance between different sources and data sets. Welcome to process hell. Only the six sigma survive.

c. Speed & accuracy

For most industries, speed and accuracy represent a trade-off. In financial markets, that option simply doesn’t exist. Bloomberg’s ability to deliver without compromising on either principle is what customers pay for.

Bloomberg’s SLA for update is the ‘same day of release’. That means for the largest 5000 companies worldwide, the entire process from being published by the company to traversing process hell to being available in the Terminal happens within the daily trading window, which globally averages 6 hours.

As the release of any financial data almost instantaneously initiates billions of dollars in new bets by automated market participants, total accuracy and reliability are an absolute must. Maintaining speed and accuracy for ever-increasing datasets and timeframes required decades of experimenting, fine-tuning and robust CI/CD frameworks.

Bloomberg's speed can pay for itself. As observed with News under Cornered Resource, a market-moving company update, reaching a Bloomberg user moments before other sources/platforms, could save their portfolio from a $30,000 nosedive. This split-second advantage reframes the Terminal from a cost into a vital investment, justifying its price tag in a single news break.

d. Data labelling

Financial systems across market participants need a way to communicate with each other, a common language that identifies the countless instruments, securities, companies and market events. Enter FIGI, previously BBGID.

FIGI is a symbology framework of over 700 million instruments, underpinned by a proprietary schema and nomenclature to accurately identify securities and instruments across asset classes and rightly associate them with their derivatives, capital events, etc. One that requires various iterations over time to account for every possible instrument type, event, frequency, and relation.

For example, imagine ‘a dual-listed, dual-share class stock undergoing a stock split in one class, having a dividend due soon after the split, announcing a year-long buyback, and calling a convertible bond outstanding.’ It is an unlikely scenario, but it is shared for illustrative purposes to draw out complexity and dependency across instruments.

Interestingly, Bloomberg made it an open and free-to-use framework, unlike its fee-based peers (RICs, CUSIPs, SEDOLs). This led to FIGI's wide adoption by exchanges and regulatory bodies as it offers comprehensive coverage and granularity and helps simplify regulatory reporting, transparency and consistency in financial transactions and reporting. By commoditizing the complement, Bloomberg removed symbology as a potential differentiator or entry point for competitors.

Adoption is so entrenched now, trying to move away from it would be akin to moving an entire country from a 2-pin to a 3-pin power plug system.

e. Depth of customer integrations

Bloomberg's data is deeply integrated into customer workflows and needs. Beyond the primary user, Bloomberg data is fed into the web of stakeholders around that user who manage, govern, monitor, or settle actions taken by the user. Many of these integrations were built long ago and interact across multiple systems. Back when limited thought was given to long-term flexibility and adaptability (i.e. 'hard-coded' fields and labels) to new data vendors (who may require new schemas and formats).

Examples of data feed integrations across usecases include:

revenue generation – proprietary modelling and back testing, trading algorithms and routing software, quantitative decision-making

monitoring – firmwide portfolio analysis, risk & exposure monitoring, compliance and trade limits,

reporting – internal or client reporting and statements, exchange reporting

It is not just customers but also third-party data providers who are deeply integrated into Bloomberg’s ecosystem. It’s a dual-sided network (explored in Network Economies). Even if someone can crack customer integrations from scratch, it would be worthless without achieving significant third-party integration. The opportunity cost for customers and vendors to entertain integrations with a new entrant is unattractive and adds to Bloomberg’s moat.

Given the complexity of interacting systems, replacing existing software or feeds if often met with high resistance from customers. Knight Capital’s $440m implosion in 2012 stemmed from a deployment error. Newcomer exchanges have had their fair share of reputational and financial damage when BATS failed to list their own IPO on their own exchange due to software bugs. Complexity and time in the market are a moat to those with a zero failure rate. It’s a high-stakes game where one error can be ruinous.

f. Others

Bloomberg also achieved process power in other parts of its business, like sales and customer support, that is outside the scope of this document, each trailblazing in its own right and hopefully not lost to history.

Growing terminals from 10 in 1981 to 350,000 in 2024 didn’t come with an average sales team or average sales culture. Delivering a CAGR of 27% for 43 straight years certainly needed some magic behind the curtains. A hard-driving sales culture with generous perks accompanied by tales of corporate lore wasn’t uncommon.

To support this exploding user base, a global 24x7 helpdesk was carefully developed and trained to pamper and indulge customers who need dedicated and instant support around the clock due to large amounts of capital at risk across multiple markets. Instant support comes in the form of punching a single keyword to be connected in real-time to a live service rep through the Terminal chat.

Very hard things to do at scale, decades before GTM playbooks were invented and standardized sales training courses were available.

3. Network economies

(value to existing and new users increases as more users join)

a. User network

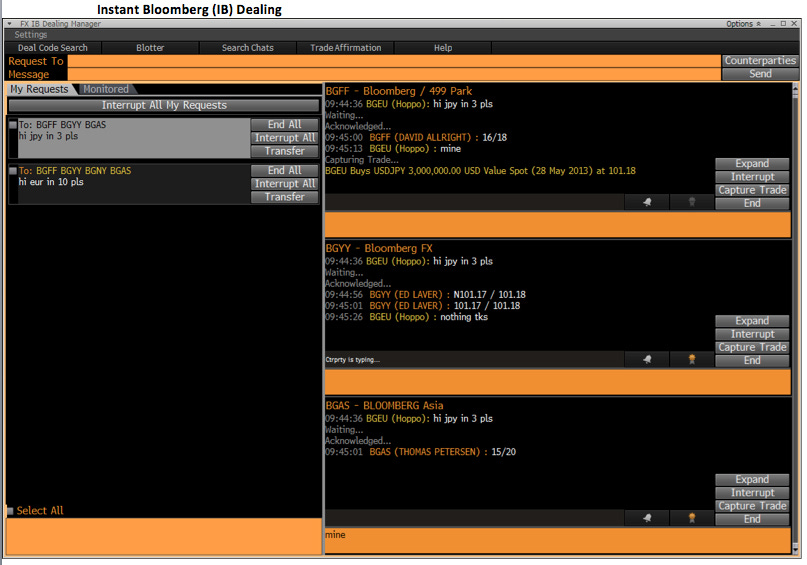

Bloomberg’s chat service (IB for Instant Bloomberg) was the first time multiple user types in the financial value chain were electronically connected across institutions. Before IB, customers, trading partners, dealers, counterparties, sales & account managers sat on different internal networks and only communicated with each other via email or phone. Through the industry’s first P2P chat in 2002, Bloomberg instantly connected all their existing users without additional software installation. Offering chat for free, making users discoverable, and providing direct customer support through IB contributed to adoption at scale. Bloomberg inadvertently created the first financial social network, unsurprisingly following the winner-take-most model.

It wasn’t long before the who’s who of industry titans were seen using it. And soon after, it wasn’t long before it became an exclusivity club. Bloomberg handles were exchanged instead of business cards. One trader was even quoted hearing, “I only date guys with Bloomberg terminals”.

A recent tweet from the founder of Jeffries, a boutique investment bank, shows just how accessible IB could be to the upper echelons of Wall St. CEO’s could ping each other outside the snooping eyes of corporate IT. Of course, a private network that the compliance department didn’t initially have access to led to some bad actors & the LIBOR scandal. But it wasn’t long before that was fixed on Bloomberg’s end.

Borrowing Buffet’s terminology, IB was the unbreachable moat on which Bloomberg’s economic castle was built. As more users joined, IB became more attractive to the have-nots. Many attempts have been made to challenge IB, none that can be considered a resounding success.

b. Pricing & liquidity

Chat as a 'free' feature attracted users, and users brought along liquidity, capital and execution. Bloomberg chat evolved to be trade-ready, which meant quotes, orders, and trades were binding, and users never had to leave the chat interface to complete a trade. Executed trades then flowed from the chat to the middle and back office for reconciliation, settlement, and records. Compliance and oversight features were also added, setting the flywheel off again.

While nobody bought a Bloomberg terminal for the chat feature (an oft-misused trope), the value of being directly connected in real-time to different liquidity pools across counterparties just by opening a new chat window was well worth the price. Trades could be completed with a single word, ‘mine’ or ‘yours’, for buy and sell. With this kind of ease, liquidity was quickly sucked away from voice-based channels. And as more liquidity arrived, it made it more attractive to the have-nots.

That kind of usage can’t have been pre-planned, Bloomberg didn’t design IB for one-word trading at the onset. They just built a great product, and then let their community of users dictate how best it should be used and what pain points to solve.

c. Distribution network

Bloomberg had a two-sided marketplace of users and data vendors (covered in more detail in Scale Economies below). Each new dataset added to the Terminal made it attractive to more users. Each new user added to the Terminal made it a more attractive distribution channel for vendors to publish their datasets.

Aggregation of supply and demand played to Bloomberg’s advantage. Not all users needed access to all the data vendors, and not all vendors were looking to sell to all users. It would have been a nightmare for users and data vendors to individually and correctly map the right 1-1 connection to each other without an introducing broker. Bloomberg made it exceptionally simple by charging a fixed price to aggregate both sides and making them equally available to each other. While the user only consumed what was needed, they could be assured that any additional need was already available somewhere in the Terminal.

A dual-sided marketplace is well-studied in the era of BigTech. It would be hard to find a non-tech company that combined Network Economy with Cornered Resources, Process Power and Scale Economies in the early 2000s well before many of these concepts were formalized!

4. Scale economies

(decreasing unit costs as volume grows)

a. Customers

With 350,000 terminals, the cost of new data/product/tech is instantly amortized across a large user base. The Terminal is mission-critical to most users, which gives it a unique advantage. Exceptionally stable demand. A conducive environment for long-term thinking and investments.

Bloomberg has only twice seen a drop in it’s userbase, once after the 2008 GFC, and another in 2016. For all other years, consistent user growth has allowed for consistent R&D investments, keeping Bloomberg on the leading edge without fearing a sudden drop in users, dampening ROI. Acquiring multiple Process Power and Cornered Resources didn’t come cheap. It took years of intensive capital investments, funded by the steady growth in users.

This user base (for comparison, Factset was 190k in 2023) also allows Bloomberg to negotiate better prices with third parties in acquiring content. As the industry leader in users and revenue, all the negotiating leverage is with Bloomberg, particularly against niche alternative data and analytics providers.

These 350k users are diversified across various financial services firm types - trading, banking, asset management, research, hedge funds, quants, algorithmic, etc. That means even niche datasets/features built for one segment can often be cross-sold or up-sold to others to be further monetized.

b. Third-party data sources

In addition to all the data it collects, produces and owns, Bloomberg distributes a range of third-party data from exchanges, dark pools, government departments, industry bodies, etc. To pull data at this scale, thousands of distribution agreements and backend connectivity were setup across vendors and asset classes (equity exchanges, FX venues, OTC aggregators, funds house, commodities houses, etc.).

The market for third-party providers is highly fragmented, with serious heavy lifting required both technically and legally. Technically, to integrate across a range of API standards, legacy systems, and data schemas. Legally, to navigate a wide range of licensing constraints, regulations, geographic nuances, and distribution limitations. The requirements varied per data type and vendor. Bloomberg made the early investments to accomplish this slow and manual endeavor. The initial capex, though, was only once. Every new customer now benefits from those investments and gets access to an ever-growing list of datasets.

Bloomberg’s scale demands lightning-fast support from its network of vendors. When hiccups occur in data feeds, a single call to the stock exchanges can set things right. This level of access and seamless communication is no accident, it's the result of a carefully cultivated symbiosis between Bloomberg and its vendors, forged through years of collaboration, navigating red tape, and nurturing key relationships.

c. Functionality

The Terminal had 15,000 functions, as estimated by Fortune in a 2013 feature. However, the average user only accesses 29 of them. Before this is dismissed as bloatware, consider that being the default OS of an entire industry requires you to cater to as many needs as possible through a singular product. Bloomberg loves to build in-house. Over time, this has added up, much like Apple, which had 12 native apps in the first iOS version, whereas that figure stands at 36 for the latest.

This wide selection reduces the need for users to buy additional products or services from other vendors, increasing Bloomberg’s share of wallet. Given the fixed price of the Terminal, unit costs for the customers reduce the more they rely on the Terminal for their varying needs. It’s a win-win.

Functionality is a form of adding value to more users. And value is part of Bloomberg’s guiding principle as best captured by Tom Secunda, a co-founder with Mike Bloomberg –

‘the firm has never been in a battle about price because it is always in a battle about value’

d. Full-service

to support the Terminal, Bloomberg offers a whole host of tools to serve users across the FS value chain. For example, enterprise data management (EDM) software allows internal firmwide decision makers, internal market data teams, risk managers, compliance teams, middle and back-office staff, as well as external counterparties and customers, to plug into a single source of information.

EDMs allow for monitoring, reporting and governance of all Bloomberg data flowing through a customer's network. These sophisticated systems serve as a central hub, ensuring data consistency and real-time quality checks. Ones with a compliance module enable regulatory checks, maintain a clear audit trail on the data used, and enhance transparency and risk management.

A vendor serving only a limited part of the user value chain is left exposed to the scale of support Bloomberg offers to all the connected users in that value chain. Scale here provides an unfair advantage that is hard to compete against given the mandatory nature of an EDM service when working with a ton of data.

5. Switching costs

(alternatives are too costly, risky and/or painful to switch to)

Switching out from Bloomberg often requires overcoming hard technical, process and behavioral challenges simultaneously, each with high capital and personnel costs.

a. Mission-critical infrastructure

As an essential tool for managing billions of dollars, replacing Bloomberg as a vendor is fraught with complexity. The mantra, ‘If its ain’t broke, don’t fix it’, applies ever more so.

Without the CIO, CTO, CDO, COO & CEO at the group, divisional, or geographic level (depending on the size of a customer) agreeing that they have a bulletproof plan and resources to undertake the gargantuan task of a like-for-like switch, no Terminals are being turned off. Switch playbooks don’t come off the shelf. One usually must be built from scratch and specific to the customer's workflows, integrations, and processes. The odds of getting it right the first time are egregiously low.

In addition to being critical infrastructure, the high complexity in customer integrations observed earlier (under Process Power) usually serves a 1-2 knock-out punch for anyone trying to displace Bloomberg. Notice that both powers symbiotically co-exist. Each can be potentially overcome alone; together, they are unassailable.

b. Workflow changes

Even if a challenger overcomes the technical wizardry of displacement without a glitch, they next need to update every supporting function, process, and policy that underpins each usecase – reporting, monitoring, risk management, calculations, computations, models, etc – that operate offline over and above systemic integrations.

Offline process updates stretch from arcane things like updating their TOS and disclaimers on their website and customer portals to account for the new vendor’s TOS and requirements to complex updates like business continuity plans for the new vendor, who may have different SLAs and customer support capabilities.

The second-order impact of replacing Bloomberg is often discovered after something goes wrong. Only one or two of these stories need to travel in customer circles, and the challenger can be doomed for life.

c. Decades of familiarity

After you've managed to update all the technical and process dependencies, you still have to retrain users who have known just one way of life for the entirety of their careers. Dealing with agents who can and will actively hate anyone ripping their beloved systems apart usually sends the challenger sales/support rep scurrying back to their desk cover. Hard as it may seem at first glance, this is probably the most thankless and scary step of the three. Not having to face a trader’s wrath is a sufficiently good and common reason for not meeting the sales quota.

6. Branding

(offering higher perceived value to customers)

Given their reliability, accuracy, and comprehensiveness, it is unsurprising that Bloomberg dominated the industry. So, without significant marketing spend, they developed a powerful brand and a loyal user base. It wasn’t long before the Terminal cultivated a cult-like following and embodied the spirit of Wall St.

Strong brands with high pricing power are often wielded into status symbols, especially in the high-octane world of trading – like Hermes ties, Patagonia vests, Tom Ford suits and Rolex watches. Having a Terminal soon became a litmus test to gauge your relevance and importance. While the status symbol is sometimes mentioned as a strength, it is indeed an effect rather than a cause of power.

Decades of familiarity breed loyalty and trust. Loyalty can border on the emotional. It is this emotional side that challengers tend to underestimate. Even if a product can outperform Bloomberg, a BIG IF, a tougher challenge awaits - convincing users to rationally evaluate the new option. Doing so is impossible without knowledge of the dark arts to hack and re-wire their neural pathways. Pathways that are practically fossilized and impervious to change.

Imagine if Samsung had to individually approach Apple users to switch to the new Galaxy phone. No one would volunteer to be a sales rep for Samsung. Fortunately for the world of consumer tech, growth is product-led or marketing-led. Enterprise tech is almost entirely sales-led. As aptly summarized by Christina Xi at Databento, building a killer product is rarely enough.

Bloomberg’s unchanging UI is intentional. Anyone can spot a Bloomberg screen instantly on any trading floor. If the users wanted the UI changed, it would have been. Bloomberg didn’t get to 350k users paying 30k each without delivering exactly what their users want. The UI is now part of the brand, and Bloomberg probably can’t change it much, even if they wanted to given some other considerations2.

With Apple-like loyalty comes Apple-like pricing power. Not pricing the Terminal at a significant premium to competitors would be foolish and self-defeating. The following section will reveal how Bloomberg’s pricing is as intentional and measured as its UI.

7. Counter-positioning

(differentiated business model that incumbents cannot/will not mimic)

This power usually applies when there is a large incumbent, and in the initial years, they were Telerate, Dow Jones & Reuters. Bloomberg's counter-positioning strategy represents a series of calculated trade-offs. Below are examples of how Bloomberg zigged when others zagged and how they benefitted from it.

a. Staying private

Staying private afforded them the patience, vision, and discipline to play the long game. The whims of quarterly earnings calls and volatile shareholder expectations did not constrain them. But that meant they also had limited access to new capital. This constraint pushed them to innovate and build in-house hardware and software stacks at a lower cost and higher output in the early days. That early ethos persisted even during periods of strong growth, giving Bloomberg high control over its architecture and leading to the Terminal’s instantaneous responsiveness despite the firehose of data, even to this day.

Meanwhile, their listed peers used their balance sheets to fund fast growth through aggressive acquisitions, price discounting, and new market entry. These options were rarely conducive to margin expansion, and Bloomberg didn’t resort to them, instead prioritizing steady long-term growth.

b. Singular product focus

For 30 straight years they focused all their attention on making the Terminal more valuable to more and more users every year. Every decision in the company revolved around increasing the value delivered through the Terminal - from launching News to their data acquisitions to their hardware and network investments. Their peers experimented with various products, services, and solutions, but none were able to deliver a better terminal than Bloomberg. Forty years on and billions of dollars in R&D later, they have yet to reach parity.

However, many of those experiments did prove to be new multi-billion-dollar adjacent markets that Bloomberg (un)intentionally missed and now play second fiddle to. MSCI & S&P captured entire new Terminal size markets in indexing, Moody’s and Fitch in credit ratings, and various others in risk analytics. Bloomberg decided to be good at one thing, and no one can fault them for achieving that goal.

c. Delight the end customer. Always.

Every seasoned user of Bloomberg swears by it. Once past the initial learning curve, the environment, the steady UI/UX, the shortcuts, the keywords, the response times, the consistency, the lack of unexpected changes, and the slow, incremental updates all cultivate a sense of comfort, familiarity and ease for the user.

Familiarity & stability are key design and engineering values at Bloomberg, as is their attention to detail. They even hired the designer behind Tahoma, Georgia & Verdana fonts to update the default Bloomberg font. Placing a high value on user acceptance and giving users adequate warning ahead of changes are some examples of user-centricity. No trader appreciates typing an extra keyword to execute a query or navigating to new locations to find info. Changes of any kind have to be slow, and the user taken along the journey, micro-steps at a time.

The users, i.e. the end customers, have been delighted by the product for so long that they often are the most prominent voice of opposition to alternate products. Few purchasing managers, finance heads or CTOs dare to stand up to a trading floor of alpha personalities and rainmakers just to squeeze out a few basis points of cost. Conversely, management were rarely fans of the Bloomberg bill.

d. Pricing by value, not feature set

The Terminal represents an abstraction away from immense complexity under the hood. Attempting to replace it with proprietary products or a collection of vendors stitched together is unlikely to yield a cost or performance advantage. So, despite its high price tag, the value Bloomberg delivers far outweighs its costs.

In the initial days, the rainmakers that used these terminals (traders and dealers) generated revenue in the hundreds of thousands per user and, in many cases, millions of dollars a year. Since then, new customer segments, such as hedge funds, quant funds, and HFT & algo traders, emerged, pushing their revenue-generating abilities even higher. Other customer segments, like asset, fund, and wealth managers, have only consolidated over time and gotten bigger, increasing their ability and willingness to pay for terminals.

To put this in context, consider NY Post’s 2016 report. JP Morgan had 10,000+ terminals at $21,000 a pop for a $210m annual tab. The operating expenses of their CIB & AWM divisions (assuming the consumer & commercial bank didn’t need Terminals) was $27.4bn (page 52). Bloomberg represented 0.77% of their opex (!!). In the same year, JPM vested/exercised $2.5bn (page 198) in stocks and options for their top employees. They had a high capacity to foot the Bloomberg bill, only their willingness waned in the post-2008-GFC paradigm of cost-cutting at banks.

0.77% is certainly an outlier for the fat tail of customers. However, the figure wouldn’t have been too different across Bloomberg’s largest clients – the major Wall Street banks and their global peers.

Staying under a few percentage points of opex for half the customer base even during the cost-cutting era, while being the primary tool for revenue generation, proved a nifty cost-benefit analysis for most bank execs.

e. Gradual, justifiable price increases

A longer-term view from 2001 to 2023 shows prices increased at a CAGR of c.2% annually. Users grew at a 4% CAGR over the same period. Very reasonable price increases in an industry where capex and opex often grow much faster than that!

For comparison, JP Morgan’s operating expenses at the same time grew from $20bn to $87bn, a 7% CAGR. Goldman’s rose from $12bn to $34bn at a modest 5% CAGR. Bloomberg ensured their prices grew much slower. When put in this perspective, it feels altogether agreeable and appears to defy some commonly held principles of economics - prices should rise at the rate of demand!

Bloomberg is among a rare breed of companies that have maintained an acute sense of their customers' capacity and willingness to pay.

One can only admire how Bloomberg's counter-positioning, while at first glance could be misunderstood, was often a source of strength and long-term vision.

8. [BONUS] Bloomberg’s Original Innovations

(early bets that delivered overwhelming customer value)

While the 7 Powers explain Bloomberg’s sources of competitive strength, they don’t explain why Bloomberg won in the first place. Much of that had to do with the innovations Bloomberg brought to market. To appreciate these, one has to consider them in the proper context. The below bets were executed in the 80s-90s before they were commonly accepted and without precedent.

The Original Cloud

While predating the term for decades, Bloomberg inadvertently created the first proto-model of the cloud by taking computational and storage load off-prem on behalf of its customers.

It embodied many core principles of modern CSPs –

delivering data and analytics through a centralized, subscription-based platform with remote access capabilities,

offering scalable, continuously updated services and specialized solutions where users can be dialed up or down

abstracting away complexity at the back end while maintaining a stable, fixed view for the user front-end

investing in specialized hardware and software exposed through a few end-points to access the world’s financial data and run workloads.

This saved customers billions in investments into on-prem hardware, software, and technicians to assimilate and ingest data from various third-party sources.

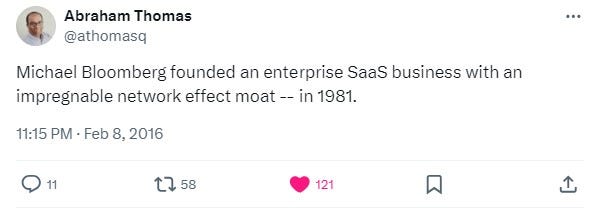

The Original SaaS

Bloomberg had the early insight that subscription fees are bundled into the expense line. In the early days, trading/banking divisions were primarily judged by revenue and gross profit (i.e. cost of revenue). Among other things, the cost of revenue consisted primarily of transaction fees. Desk heads would fight tooth and nail to route trade through lower-cost strategies and systems but rarely paid attention to opex (that responsibility was much higher up the chain). So, Bloomberg catered to the specific circumstances of their primary purchasers and didn’t charge commissions for trades through its platform; instead, it built a commercial model that charged to opex. Bloomberg played the long game, realizing that subscription fees – relatively low compared to the revenues trading desks were making – would make for a perpetual cashflow machine.

The Original Big Data

Bloomberg was among the first to realize the need for a high throughput data processing system. The company's Ticker Plant, an engineering marvel, emerged as the cornerstone of Wall Street's information age, a system capable of ingesting a torrent of global financial data, processing it in microseconds, and delivering it to traders faster than they could say "buy low, sell high".

”It’s the beating heart of Bloomberg’s data estate, processing over 200 billion pieces of financial information and publishing them in real time...every day.

Every piece of market data is about the size of a tweet, but there are millions of them per second at the peaks of the day…

We need to route them out around the world to customers. And this entire process needs to happen in microseconds.”

The Ticker Plant's significance extends beyond mere speed. It manages data variety and volume that would challenge even today's tech giants. From real-time stock prices to breaking news, this infrastructure serves as the central nervous system of global markets from New York to Tokyo.

In addition to ingesting, sorting, storing and distributing this raw information deluge, Bloomberg pioneered big data analytics in finance, providing the early GUIs for graphing and analyzing financial data on the fly (novel then and far beyond any competitor). This early mover advantage was built on as more instruments and security types entered the market, making the Terminal then the first port of call for complex data wrangling needs.

Some argue that Bloomberg was the original social network, but that stands true only in the domain of finance. Some would even argue it may have been the precursor to the internet. It is beyond the scope of this article to defend that. What should be pointed out is that Tim Berners-Lee created the World Wide Web in 1990, while the first Terminal (then the Market Master, which let you access real-time information from outside your network) was delivered in 1982(!!) Someone with more dedication and access to historical records may have better luck finding a ‘B2B-cloud-based-SaaS’ that predates 1982.

Does this make Bloomberg INEVITABLE?

Bloomberg's dominance is a testament to the symbiotic interplay of its Seven Powers and the constant customer value they deliver. To challenge Bloomberg is to compete with a tightly integrated, self-reinforcing system of advantages.

So it's certainly tempting to view the company as Thanos with all his Infinity Stones. Bloomberg with ALL the Seven Powers appears to be unkillable. Inevitable.

But that is not the conclusion I want to leave you with. Let's pause and reframe our perspective.

Markets & capitalism are dynamic and not zero-sum. Bloomberg’s dominance while formidable is not absolute or permanent. The rise of MSCI (with indexing), Moody's (with ratings), Morningstar (with funds), ICE, S&P Global & Refinitiv-now-LSEG (various), suggests there is room for innovation and growth alongside Bloomberg’s empire.

Challengers need not aim to dethrone the titan. There are always adjacent opportunities in complementary or new markets to pursue. New niches emerge as markets evolve, creating space for innovators to lay claim to their Gauntlet. We live in a Multiverse after all (there is only once more MCU reference, I promise).

What if we are asking the wrong questions - 'Why is it hard to kill Bloomberg?', or ‘Can Bloomberg be toppled?’. Questions that ignore a key premise (i.e. it is needed) and hopes for an impossible conclusion (i.e. it is possible). No one is asking for Bloomberg to be killed, certainly not the vast majority of its users and customers.

So, what question should the aspiring entrepreneur be asking instead? Maybe these can serve as a start –

What emerging niches in financial data and analytics are ripe for disruption?

What underlying structural trends is Bloomberg not ready to capitalize on?

Where are the barriers to entry for new entrants reducing?

What customer segments are Bloomberg ignoring? What customer pain points would Bloomberg's broad approach overlook?

What unique combinations of data, analytics, and user experience are needed to create the next great financial tool?

Remember, the future of financial data and analytics is not a battle for supremacy. It is a race to innovate, capture new market opportunities and remain a micro-step and milli-second ahead of your peers. Consistently. For Decades!

Don’t try to slay a giant. Find new fertile ground to plant new seeds. The opportunities are out there, and some have already been seized. In the next edition, we’ll look at some of them. So stay tuned and stay curious.

If you got this far, thanks for reading my first post!! I do hope you found some value and learnt a bit along the way. Feel free to comment with questions, corrections or suggestions. We can both learn through this series.

If you liked this post, please do 4 things straight away:

Share it with a friend who is as interested in this topic as you are.

Follow me on Twitter for short form sound bites: @TheTerminalist

Hit the like button, it feeds the hungry algorithm.

Subscribe to receive more of my work. Your work emails quite welcome, as it helps me tailor my content to my readers.

Until the next one… to the builders and founders brave enough to enter this market…

The Terminalist

Edit - if you enjoyed this deep dive, you’ll also love my next three post:

The first looks at the industry through the eyes of three different companies, CME, FactSet & MSCI to draw out the three stages of the value chain and why they accrue value differently.

The second looks at why the industry generates above average returns and how the nature and type of financial data influences the economics of various market participants.

The third looks at why a new frontier has opened with LLMs that has the potential to challenge the legacy terminal architecture that struggles with firm and user context

Further Reading

A recent reddit thread that prompted my article, with thoughts from users, founders and ex-employees. More from ycombinator here, here and here.

@MattTurck’s short synopsis as a VC in 2014 that still stands true today. Don’t skip the insightful comments from (some successful) challengers of that time.

@BryneHobart’s 2019 breakdown on what it would take to challenge Bloomberg.

@MarkRubinstein’s overview of where Bloomberg faces critical mass challengers

@FrederikGieschen’s succinct history of Mike Bloomberg’s entrepreneurial journey.

Broad media that have questioned Bloomberg’s staying power - Institutional Investor, New York Times, CB Insights

This bit is more devious than it appears. Assume Vendor A is building a Product X for Client C that does some price analysis. This product X needs access to market data to function. Client C already pays for this market data for other internal products they use. They can’t simply plug this data into Product X now. Product X is owned and operated by Vendor A, who, according to the data licensing frameworks, has to pay separately for the data needed to run Product X. Even though Vendor A isn’t using Product X, and Client C, the ultimate user, already pays for this data.

No points for guessing who engineered the data licensing frameworks to work this way. There is, however, a solution. Vendor A could avoid these costs by building Product X to be fully deployable on Client C’s servers. If the product appears to be owned and operated by Client C, only Client C pays. Easier said than done when the world is moving towards serverless architecture.

There are also some technical reasons why Bloomberg hasn’t changed the UI/UX. Maintaining ultra-fast responsiveness has some trade-offs, but we can save for another day

Great piece! I used to work there many years ago and the culture is fascinating. Just a relentless focus on cramming as much value into the terminal as possible. The sticker price may seem high but as you note it is mission critical and arguably trivial compared to what’s at stake for their target customers - e.g. you are paying your traders millions, so $25K/year or whatever the going rate is, is not really a factor.

Talent mentality is also interesting. Maybe things have changed, but it my day it was bare minimum 10 interviews to get in the door and then weeks of classroom training before you could touch anything. And then more ongoing training for as long as you are there.

An analogy might be a pro sports franchise - a maniacal focus on the best talent and obsession with winning.

Great overview. I first saw Bloomberg terminals appearing in the '80s the hardware was very futuristic-looking indeed.

Your comments on their service levels are spot-on. For the per-seat price they'd better be ;-) In fact, their high price has turned out to be a sort of Giffen Good https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giffen_good , with an aspirational element that is almost unmatched.

Like the HP-12C financial calculator, the arcane user interface (it still looks very old-school") becomes a bit of a "secret handshake club".

Another key lock-in element over time is their introduction of integrated trading systems. Once that's chosen as a firm-wide standard, the switching costs become prohibitive indeed.