Walk onto any modern trading floor, and you'll encounter faceless servers humming with algorithmic precision, machines and bots conversing in an electronic symphony of bewildering complexity. The mathematics and computer science behind it incomprehensibly advanced. The seemingly serene setting, a thin veil hiding the immense and frenetic chaos of global financial markets.

Step back twenty years, and the chaos was visceral. Hundreds of brokers screaming into headsets. Hand gestures wildly signalling to each other. Eyes darting between dizzying arrays of screens while ticker displays defy gravity overhead. Wearing colour-coded jackets like coaches at some financial Super Bowl, their incessant activity somehow translated into orderly financial markets.

In both cases, each a contradiction to the other, you'd be right to ask - what problem is all this complexity actually solving? The answer lies not in glass towers or silicon chips but surprisingly in a medieval inn in Bruges, where a family of innkeepers accidentally invented the blueprint for every financial exchange that followed.

We all know broadly what stock exchanges do, yet that knowledge can feel hollow when faced with the complexity and sophistication of modern markets. Both of which are on an incessant march upwards.

This post is the first in a series that breakdowns modern exchange infrastructure by studying the great exchanges of the past and tracing the evolution of markets from their medieval origins to their digital future. Through this historical detour, we’ll explore how and why the systems we take for granted emerged, and whether they're still fit for purpose as markets, needs and expectations evolve.

Our journey starts 700 years ago in a Flemish inn, with a tale that has long faded from our collective memory, but not our language. The innkeeper's family name still survives in our lexicon - ‘bourse’ for stock exchange derives partially from the Van der Beurze family that ran the inn1!

History often celebrates majestic cathedrals and artistic masterpieces, but one of humanity's most consequential innovations - the world's first financial exchange - emerged from a simple family business. Its financial ecosystem has lasted through the centuries, carrying the institutional DNA that still shapes markets today from London to New York. Today, we find out how.

You’d be right to think, ‘Wait, why Bruges, and why was an innkeeper involved?’. Fret not. The post is structured to answer just that through the following sections:

Crossroad of Commerce looks at the confluence of factors that made Bruges uniquely positioned to form an exchange in medieval Europe.

Inn of Innovation describes why opportunity came knocking at a modest inn rather than the court, city council or aristocratic enterprise.

Tavern to Trading Floor charts the early steps of the inn and its transition towards an organised exchange intermediated by trusted middlemen.

The Merchant Market explores the inflection point as the exchange took off and the contributing assets that dramatically unlocked trade and wealth.

Peak to Pause surveys the impact of free markets on the city and the reasons the torch had to be eventually passed on.

Exchanged DNA finally reflects on the timeless contributions Bruges made that still bear on modern exchanges and digital upstarts.

Before we dive into the captivating and unsuspecting events that shaped our history, first, a note to readers.

I am not a historian, and I don’t intend to be. The research behind this piece represents my best knowledge and interpretation of available sources2. Where precise dates and sequences are difficult to establish, the essay aims to be approximately right rather than precisely wrong.

The early drafts began as one post to offer a 'brief history tour’ of how we got to modern exchanges, from Bruges to New York. Curiosity got the better of me, and it has now evolved into a multi-part series that examines the who, how, what, why, and when of each pivotal moment in exchange history.

By studying this history through a modern market practitioner's lens, the series aims to uncover important lessons about market structure, exchange design, and financial innovation that traditional historical accounts don't emphasise. In doing so, we’ll surface some new perspectives to help us better understand and appreciate the enduring value of financial exchanges.

Crossroads of Commerce (1128-1285)

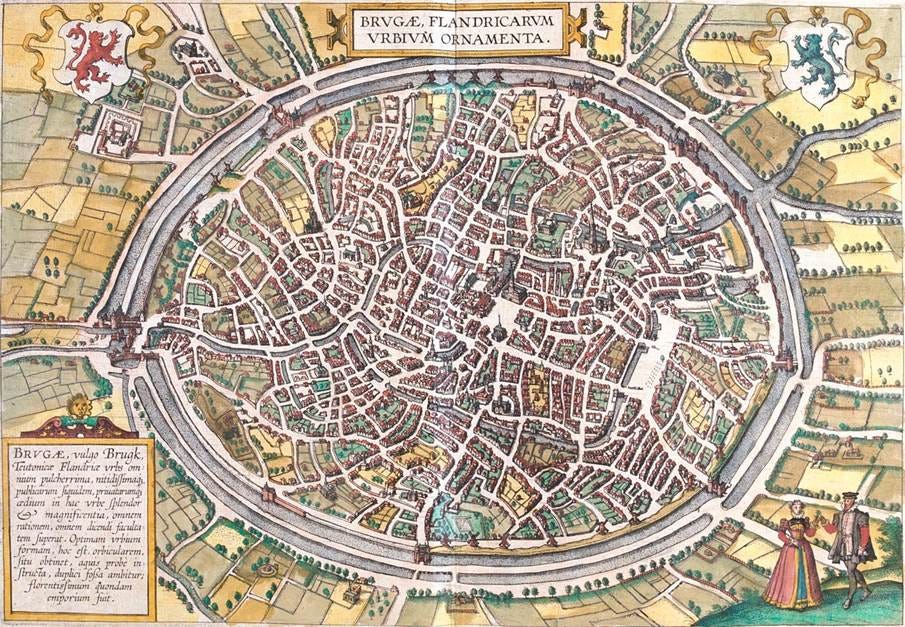

In the early 12th century, Bruges was merely one modest town among many dotting the Flemish landscape—a settlement of wooden structures and narrow streets with little to distinguish it from its neighbours. The transformation from this unremarkable beginning to becoming medieval Europe's most vital commercial centre began with a key political decision, subsequently sealed by nature's dramatic intervention.

A flood of fortune

In 1128, the Count of Flanders3 granted Bruges its city charter, providing the autonomy and trading privileges that set it apart from settlements still bound by traditional feudal restrictions. With this newfound freedom, local leaders could develop the city in response to commercial needs rather than aristocratic or religious whims. An advantage would prove essential in the decades ahead.

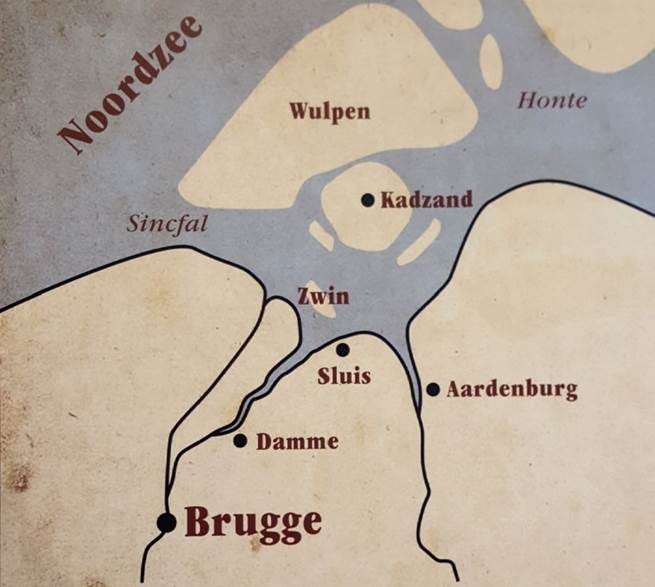

Yet political autonomy alone would not have been sufficient without nature's sudden providence. The coast of Flanders, with its shifting sands and tidal inlets, had always been vulnerable to the North Sea's temperamental moods. In 1134, disaster struck neighbouring communities when a catastrophic storm battered the Flemish coastline. In the devastation, the violent waters reopened the Zwin tidal inlet that had silted up for decades, restoring the crucial waterway connecting inland Bruges to the open seas.

The geographic windfall positioned the city at the perfect nexus between two great commercial spheres of Europe: the influential Hanseatic League4 to the northeast and the rich Italian merchant houses of Venice and Genoa to the south.

Riding the tide

Recognising their strategic position, Bruges' alderman (the city leaders) leveraged their charter-granted autonomy to build the infrastructure of international trade. The city developed a network of canals and roads connecting to nearby outports like Damme and Sluis, creating one of the most accessible trading hubs in Northern Europe.

Pushing the privilege of commerce, Bruges soon secured valuable staple rights—a legal decree from the Count mandating that incoming goods like wool, metals, and spices be sold exclusively within the city rather than simply passed through. This created a compulsory trade depot that centralised buyers and sellers, concentrating European commerce within the city's walls.

By the 1280s, responding to merchant complaints about fraud and inconsistency, the city standardised weights, measures, and currency exchange systems throughout the region. A transparent legal framework administered by city aldermen and notaries was developed that allowed various merchant houses and trading blocks to self-govern their participants. These reforms created trusted commercial standards while granting foreign merchant communities autonomous legal status under their own laws5.

Perhaps most remarkably, Bruges maintained relative political stability during the endemic Anglo-French conflicts that repeatedly disrupted commerce elsewhere. The regional rulers—first the Count of Flanders, later the powerful Dukes of Burgundy—provided military protection for trade routes against piracy and disruption in exchange for healthy tax revenues. The political neutrality enabled simultaneous trade with multiple powers in an age of frequent warfare, creating an oasis of commercial predictability—a rare and valuable commodity for merchants risking their fortunes on long-distance trade.

Europe’s purse strings

These advantages transformed Bruges into the essential meeting point between Europe's major commercial powers. The Hanseatic League brought Baltic furs, grain, timber, and copper from the north. Italian merchants offered Mediterranean spices, alum, and luxury goods from the south. English traders provided wool that fed the flourishing Flemish textile industry, creating a demand cycle that drew raw materials in and sent finished goods back out to European markets.

As trade concentrated in Bruges, its demographic composition changed dramatically. By the early 14th century, approximately 20% of the city's population consisted of foreign traders—a level of cosmopolitanism unmatched anywhere in Northern Europe. Many merchants organised into nation houses, quarters that functioned as early hybrids between consulates and departments of commerce, each with distinct legal statuses. This concentration created powerful network effects that soon would run into scaling challenges as thousands of traders converged on Bruges.

As the density and flow of trade increased, so did the need for a centralised mechanism that organised the increasingly fragmented, inefficient and disorderly commerce. Merchants from different nations typically stayed in separate quarters, spoke different languages, used different currencies, and followed different commercial customs. A Venetian trader might spend days locating a Hanseatic merchant interested in his goods, negotiating through multiple interpreters, and struggling to agree on basic terms.

Bruges needed an intermediary institution to bridge these divides and create a trusted marketplace where commerce could flourish. Into this chaotic but prospering world stepped in a family of innkeepers whose name would become synonymous with financial markets worldwide.

Inn of Innovation (1285-1309)

Location, location

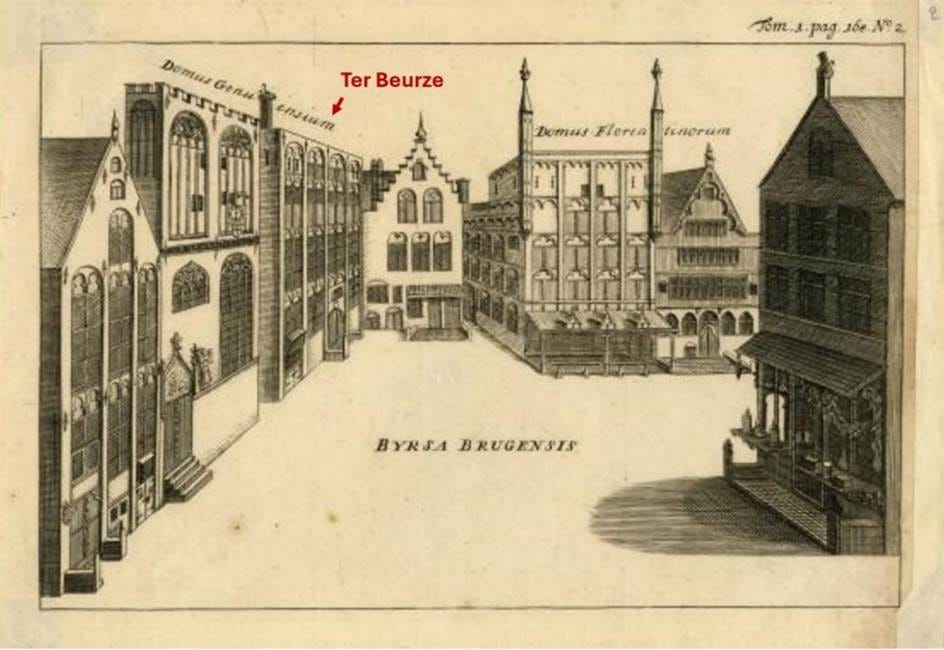

In 1285, the Van der Beurze family established the Ter Buerse inn on what would later become known as Beursplein (Exchange Square). Their choice of location was astute—positioned between the law courts, foreign nation houses, and the public square. The Van der Beurzes placed themselves at the physical crossroads of legal, diplomatic, and commercial activity.

This strategic positioning allowed them to observe firsthand the friction points that plagued international trade. Day after day, they witnessed the same frustrations: Italian merchants struggling to communicate with German traders, valuable goods sitting vulnerable in temporary lodgings, and deals failing because parties couldn't bridge basic cultural and trust divides. What distinguished the Van der Beurze family from other innkeepers was their recognition that they could solve these problems.

Trusted intermediary

They began by addressing the most immediate barrier to trade: language. The Van der Beurzes retained staff fluent in the major commercial languages of Europe—Italian, German, French, and English—enabling them to serve as linguistic bridges between different merchant communities. This transformed their inn from a simple lodging house into a communication hub where deals could be negotiated without a sequence of interpreters.

The family recognised another critical need as merchants began congregating at the inn for its communication advantages. Traders staying in Bruges often carried substantial goods and funds to conduct their business, creating security risks. The Van der Beurzes began offering secure storage for merchants' money and goods during their extended visits. Over time, their multi-generational presence and growing political standing in the city provided assurance that other establishments couldn't match, making their inn the natural repository for valuables.

The mingling of diverse merchants also created an unexpected opportunity. The inn became a natural hub for collecting and disseminating crucial market intelligence—exchange rates between various currencies, news of arriving shipments, and information about conditions in distant markets. In an age before printing presses or public news sources, this concentration of commercial information made the Ter Buerze a focal point for any visiting merchant. The flywheel was set in motion.

Credit where it's due

The family's role as trusted custodians of goods and funds naturally evolved into something more sophisticated. As merchants conducting business through the inn began to know and trust the Van der Beurze family's reputation and judgment, they started requesting credit guarantees for transactions between previously unknown parties. A German merchant might not trust a new Venetian trader's promise to pay, but he would accept the Van der Beurze family's guarantee of that payment. This trusted intermediary function expanded commerce beyond established merchant relationships to include previously unconnected parties—an early form of central clearing and settlement.

The family's financial innovation accelerated as they recognised that money could move faster than ships. While a Venetian ship might take months to reach Bruges, a promise to pay could traverse European cities in weeks. They began extending credit for pre-shipment financing, enabling merchants to conduct transactions without waiting for cargo to physically arrive. This breakthrough accelerated commerce by untethering financial activity from the cargo, creating liquidity even when goods were still at sea.

Mayor and financier

As the inn became the hub for international trade and financial transactions, the family’s wealth and reputation grew. With this increased status, members of the family began to assume civic roles, including some instances of serving as mayor of Bruges, creating a unique fusion of commercial expertise and political authority.

As mayors, they could establish the regulatory frameworks that supported their commercial activities. As innkeepers, they had unique access to information, trade networks, and influence over the city’s economic life. This combination enabled them to provide the common trust layer that allowed the city's natural advantages to flourish.

The stage was set for the world's first financial exchange to emerge. The practical innovations of an innkeeper's family—born from daily observation of merchant frustrations—were about to transform Bruges.

From Tavern to Trading Floor (1309-1350)

By 1309, the innovations pioneered by the Van der Beurze family had reached a critical threshold. What historians recognise as the formation of the exchange occurred not through any royal charter, state ordinance, or grand declaration but through the quiet adoption of standardised practices by merchants who had come to depend on the services and structure the family provided.

The exchange emerges

As trade volumes expanded, merchants required more structured systems to conduct business efficiently. The daily sessions of mercantile exchange at the inn had already replaced the seasonal, fair-based trading that characterised medieval commerce elsewhere in Europe. This shift from quarterly gatherings to year-round trading in a permanent venue created new and frequent trading opportunities, incentivising market activity.

Driven by practical necessity, the exchange established some operational practices. Fixed trading hours were set between 11 am and noon, signalled by the city bells. Gathering all interested parties at a specific time created a daily rhythm of commerce that concentrated market activity, improved price discovery and increased efficiency.

As the need for physical space expanded to accommodate growing merchant crowds, trading activity naturally migrated from the inn's interior to the open courtyard—the Beursplein. Transitioning from private, inn-bound commerce to public, square-bound trading. The communal atmosphere created space for another revolutionary practice: open-outcry bidding. Rather than privileged, bilateral negotiations conducted in secluded locations, transactions increasingly took place through public auctions, with merchants calling out bids and offers in full view of the market.

Within this expanded space, the Van der Beurze family introduced transparent posting of exchange rates for major European cities. These visible pricing boards dramatically reduced information asymmetry. Instead of a few well-connected merchants knowing what a florin was worth in Paris or Venice, the real exchange rates were posted for all to see—like a medieval Terminal carved in wood. Merchants made more informed decisions based on current market conditions, reducing friction and cost.

The exchange balanced openness with order. Unlike the exclusive guilds that dominated other aspects of medieval commerce, it welcomed qualified merchants regardless of origin while maintaining sufficient controls through bailiffs to prevent disruption. With these few unremarkable steps, the world’s first exchange took form, physically and conceptually.

Rivals and reckonings

As the city's prominence grew throughout the region, Bruges faced its first serious competitive challenge. A rival exchange emerged in Sluis, positioned to capture trade further upstream on the Zwin before goods arrived at Bruges. The city's response was as medieval as you can imagine. In 1323, Bruges deployed military force to destroy the competing exchange at Sluis under the guise of enforcing its staple rights. Through state-sanctioned warfare, Bruges demonstrated that the city would use all available means—including violence—to maintain its commercial monopoly. A powerful disincentive that worked well for decades to come.

The system's resilience would face a grave internal test soon after. In 1351, Laurens van der Beurze, the family patriarch who had been instrumental in extending (unlicensed) banking and financing services alongside the exchange, had an untimely death. Laurens was an innkeeper, not a banking extraordinaire (like the Medicis to come). Accounting standards had yet to be formalised, as was the concept of segregation of funds and succession planning. His unexpected death meant that merchant funds became entangled in estate litigation, leading to a custodial crisis. Bitter conflicts emerged between local creditors and foreign merchants.

The dispute exposed a gaping vulnerability: how could a system built on the expertise and reputation of a single family continue without its founding members? The system would need new forms of trust for self-sustenance.

Merchant Market (1350-1450)

Unbeknownst to anyone, the market's invisible hand had taken over. Self-sustenance emerged from the exchange’s four decades of operational history. In that time, trading practices, financial instruments, and merchant networks had developed sufficient structural integrity. The market was already transitioning to collective governance through consensus rather than individual authority. Consensus resolved the custodial conflict, and the death of Laurens sealed the shift from Ter Beurze to the bourse, representing a linguistic as well as a conceptual shift.

Self-governing markets

Collective governance took various forms. The cornerstone of this system was legal pluralism through the nation houses. Instead of forcing Venetian merchants to follow Flemish law or German traders to adopt Italian customs, Bruges allowed each merchant community to operate under their familiar legal traditions within dedicated spaces. A Venetian trader accused of fraud would face judgment under Venetian commercial law, administered by Venetian merchants who understood both the specific allegations and the broader context of Venetian business practices.

But how could merchants from radically different legal traditions trust each other's commitments? The answer lay in collective responsibility. If an individual Venetian merchant defaulted on obligations, the entire Venetian merchant community in Bruges could face consequences—from restricted trading privileges to selective exclusion from the exchange. Merchant communities thus had strong reasons to monitor and discipline their own members.

For complex disputes that couldn't be resolved through consensus, Bruges developed specialised commercial tribunals known as the Vierschaar. Staffed with judges experienced in international trade, these courts operated independently from general civil courts and could resolve disputes quickly, often within the square itself. This efficiency reduced transaction costs and created greater certainty for international traders.

Perhaps most importantly, Bruges formalised credit reporting through its protest system. When merchants failed to honour bills of exchange or other commitments, these defaults were registered with notaries who maintained records accessible through the European trade network. A merchant who defaulted in Bruges might eventually find himself excluded from trading opportunities in London, Antwerp, or Venice as word of his unreliability spread.

The effectiveness of this governance system rested on its overlapping enforcement mechanisms—legal, communal, and reputational. A merchant who violated agreements might face formal legal action in specialised courts, exclusion from their national merchant community, and reputational damage that limited future opportunities. The multi-layered approach created powerful incentives for honest dealing while maintaining the flexibility that international commerce required.

The great financial abstraction

The stable governance framework that emerged after the Van der Beurze family's departure created the perfect conditions for financial engineering. With reliable legal systems, quick dispute resolution, and effective credit reporting in place, merchants began experimenting with increasingly sophisticated ways to conduct business.

Breaking free of the physical

A radical breakthrough of the time came from recognising that money and hence, value need not be bound to physical coins. Italian banking families like the Medici and Borromeo - drawn to Bruges by its concentration of capital and stable institutions - brought with them scriptural money systems. Instead of merchants moving heavy bags of coins across Europe at personal risk to pay for transactions, simple ledger entries could now track payments and account balances. When a Venetian merchant owed money to a German trader, who in turn needed to pay an English wool supplier, the Italian bankers could settle all obligations with a few pen strokes in their accounting books. Value was transferred, debts were cleared, and commerce flowed without the cost and risk of moving coin, eventually converting most payments away from physical form.

Money could now exist primarily as recorded information, allowing merchants to conduct larger transactions with less risk, move value across greater distances more quickly, and deploy capital quickly for emerging opportunities. The baseline velocity of medieval trade had just increased by an order of magnitude.

Breaking free of the personal

Building on this foundation, the exchange attracted anonymous bearer instruments that took abstraction even further. Traditional debt had always been tied to specific individuals—Giovanni owes Marco fifty florins, recorded and enforceable against Giovanni personally through the debt certificate that registered debtor and creditor. However, the new bearer certificates functioned differently: whoever physically possessed the document owned the debt, regardless of their identity.

Debt became easily transferable and hence easily tradeable. A Hanseatic trader could now sell his claims against a Portuguese merchant to a Spanish buyer without involving courts, witnesses, or elaborate legal proceedings. Transferability before maturity meant that debt had to be repriced during its term. The price fluctuated based on amount, duration, discounting rates and general credit availability. A new asset class was born, demonstrating that financial value could exist independently of personal identity.

Breaking free of the temporal

The third breakthrough freed commerce from the constraints of immediate certainty and present time. Merchants developed standardised contracts for goods with specific quality, quantity, and delivery terms months in advance. These forward contracts allowed traders to manage seasonal fluctuations and price volatility. A Flemish cloth manufacturer could agree in January to purchase English wool at a fixed price for delivery in June, protecting himself against spring price increases while giving the English supplier guaranteed sales and predictable revenue. Both parties reduced their exposure to uncertainty while creating a new market for risk-takers who specialised in managing these timing risks.

Marine insurance contracts took this concept further by distributing the dangers of long-duration (and distance) shipping across multiple parties. Rather than one merchant facing catastrophic loss of shipwreck or piracy, the risk could be spread among dozens of merchants, each accepting a small, manageable exposure in exchange for a premium. Uncertainty became a tradeable commodity that could be priced, bought, sold, and managed6.

Opportune convergence

Bruges cannot claim to have invented these abstractions—forward contracts existed in ancient Mesopotamia, marine insurance emerged from Genoese merchant circles, and bills of exchange developed through the Medici banking network. The city's unique contribution lay in serving as the great magnet, attracting these dispersed financial techniques and mingling them together at renewed scale and sophistication while providing the institutional framework to formalise, standardise, and trade them.

The cumulative effect of breaking the constraints that had previously limited commerce to physical, present, and local transactions was revolutionary. The tinder for financial arbitrage was lit. Traders began exploiting interest rate differences between cities using nothing but transparent exchange rates, paper instruments and ledger entries. Financial profits could now be generated from trading representations of value rather than tangible goods themselves. (Yikes!)

Peak to Pause (1450-1531)

The height of power

The convergence of institutional stability and financial innovation produced extraordinary results. By the mid-15th century, Bruges controlled approximately 80% of the Hanseatic cloth trade and handled 40% of European commerce. In a city of roughly 45,000 residents, an extraordinary 20% of the population were foreign merchants.

Bruges' economic importance attracted diplomatic attention. Major European powers maintained permanent representatives in the city. These functioned as early intelligence networks providing advance notice on developments that might affect trade routes, currency stability, or competitive threats.

The commercial success transformed Bruges into one of Europe's most magnificent cities, giving way to a cultural flowering well before the Renaissance. Merchant wealth funded majestic guild halls and soaring landmarks - like The Church of Our Lady7 and the striking Belfry of Bruges - signalling to approaching merchants the city's prosperity. The concentration of wealth attracted leading artists like Jan van Eyck (of Arnolfini Portrait fame), whose masterpieces decorated merchant homes. The city's cultural reputation slowly became a form of soft power that drew wealthy clientele who often remained to explore business opportunities.

Over two centuries, the exchange had powered the city to unprecedented prosperity. Bruges seemed invincible. Yet, within a single generation, this commercial empire would crumble with stunning speed. The same forces that had elevated Bruges to dominance—geography, politics, and merchant networks—would conspire to destroy it.

Destiny’s undoing

The Zwin waterway, which miraculously opened Bruges maritime access three centuries ago, began sealing the city's fate. By 1480, catastrophic silting rendered the channel increasingly impassable for the larger vessels now dominating international trade. Desperate dredging efforts proved futile against nature's inexorable process. Merchants watched their costs multiply as goods required costly overland transport through compromised outports. Each additional handling slowly bled away Bruges' competitive advantage. Its geography was transforming it into a liability.

At the same time, the political protection that had sheltered Bruges' commercial empire was crumbling. The last Burgundian duke died in battle in 1477, and his daughter’s marriage to Maximilian of Habsburg (architect of the Habsburg dynasty) shifted political and economic priorities from Bruges to Antwerp.

The city didn’t take well to the new ruler. Between 1482 and 1492, Flemish revolts against Maximilian created precisely the uncertainty that international merchants could not tolerate. In retaliation, Maximilian ordered foreign merchants to relocate to Antwerp, a forced move that dismantled Bruges’ merchant networks built over generations.

This political realignment coincided with new Portuguese maritime discoveries that fundamentally altered European trade patterns. Beginning with Vasco da Gama's voyage to India in 1498, new direct sea routes from Portugal to Asia bypassed the traditional Mediterranean-to-Flanders corridors that had been the lifeblood of European commerce.

With the trifecta of external forces bearing down, Bruges' institutional pillars began to collapse in rapid succession. Portugal's 1511 decision to redirect the Asian spice trade to Antwerp severed Bruges from the emerging global economy. The Italian banking houses followed in 1516, taking centuries of financial expertise to more promising markets. The Hanseatic League's final departure in 1519 removed the last remaining stronghold of the city's commercial ecosystem.

The demographic consequences were stark. As its economic foundation crumbled, Bruges' population plummeted and its foreign merchant population collapsed. Each departure reversed the network effects that had made the exchange function—fewer counterparties, reduced liquidity, diminished market intelligence, and weakened credit networks.

The exodus was fatal. Bruges never recovered.

Yet, surprisingly, the advances it had pioneered migrated intact to more hospitable environments. The institutional memory, expertise, and merchant relationships that had animated its exchange relocated to Antwerp, carrying forward the trust mechanisms, trading practices, and financial innovations instituted in the courtyard of Ter Beurze Inn.

Exchanged DNA

While Antwerp offered superior geography, stronger political backing, and connections to emerging global networks, its real success lay in recognising and preserving the essentials of an exchange. They decoded exactly what made Bruges work.

The architecture of trust

The transformation of trust represents perhaps the most profound innovation to emerge from Bruges. The process evolved through three distinct phases, each representing a more sophisticated approach to the fundamental challenge of enabling commerce between strangers.

In the earliest phase, personal trust prevailed. The Van der Beurze family built their reputation through direct relationships with individual merchants, multilingual staff who could bridge cultural gaps, and physical custody of merchant assets. This system worked well within the intimate scale of medieval commerce, where the same families conducted business across generations and reputation was built through face-to-face interaction.

The formalisation of the exchange marked the shift toward procedural trust. Trading bells that signalled market hours, standardised documentation for bills of exchange, and public price boards displaying currency rates created reliability that didn't depend on personal relationships. Trust became embedded in consistent procedures rather than individual personalities.

The third phase emerged when the founding family stepped back. The exchange operated through merchant custom, collective incentives, established legal frameworks, and adopted new financial instruments independent of individual actors. The system had achieved systemic trust—confidence in the design and structure of the markets, beyond just procedures themselves.

The progression from personal through procedural to systemic trust became the template for all subsequent financial exchanges, and still holds today8. Yet trust alone wasn't enough. Bruges had to solve equally fundamental challenges of market operation, establishing timeless principles that all financial exchange must follow:

harness network effects – concentrate activity/liquidity to attract new buyers and sellers in a positive flywheel

reduce information gaps – ensure information parity and fairness across all market participants

protect against bad actors – establish sufficient mechanisms that effectively neutralise or eliminate illicit behaviour

reduce friction – foster innovation by providing a conducive environment to solve commercial problems that unlock capital efficiency

Immutable pre-conditions

The hallmark of these innovations drew not from their specific medieval implementation but their conceptual completeness. Completeness that, seven centuries later, challenges modern markets.

Today's new digital exchanges grapple with remarkably similar issues, merely clothed in different technology. How do you create systemic trust in decentralised trading networks of unknown participants? How do you harness network effects when participants can trade across multiple venues simultaneously? How do you incentivise honest dealing without overlapping enforcement mechanisms?

Not realising how the timeless principles apply can (and have) lead to destructive outcomes.

Incumbent exchanges face parallel dilemmas. How do you improve price transparency while maintaining competitive advantages? How do you price market data to expand long-term market participation rather than maximise short-term revenue? How do you govern new financial instruments without succumbing to speculative trends that may prove ephemeral?

For anyone seeking to decode the architecture of modern finance or design the exchanges of tomorrow, answers to these questions lie in uncovering the lost principles and value layers buried deep in the history of great financial exchanges. Today we’ve uncovered a few. There is plenty more to discover.

Next stop, Antwerp!

Until next time, keep building...and don’t miss (#4 of) the further notes section below.

The Terminalist

h/t - to Claude Sonnet 4 for help with editing.

This substack continues to be free only with your shares, reposts and likes. So be generous, and gift the free subscription to those in your network :)

If it’s your first time here, hit subscribe for a welcome email that highlights my previous posts.

I’m now on LinkedIn, with zero followers or connections. Help me get off the ground, by connecting and linking to my profile in your reposts. If X is your jam, follow me there.

Further Notes

I've researched extensively to ensure accuracy in framing, narrative chronology, and causal factors. Pardon any mistakes, and do write to me with corrections.

The history of exchanges and other modern financial constructs offers revealing insights for today's builders. If you enjoyed this historical detour away from my usual business model and value-chain focused posts, please let me know if you want more through your likes, shares and reposts.

The Terminalist community has crossed 3,000 engaged readers! You represent founders, builders, VCs, asset managers, PMs, engineers, retired executives, and seasoned operators (and CxOs) spanning sales, product, tech, data, and financial services. Thank you for your continued support and encouragement.

Eikon is finally being sunset, burying with it a tale of incredible struggle chasing the industry icon. Its owners - Reuters, Thomson Reuters, Refinitiv, and now LSEG - never figured out what to do with it. It burned through billions in capex, churned through hundreds of executives, and was persistently stuck as second-rate. Its decades long meltdown is an undocumented story worth telling as it offers crucial lessons for innovators disrupting its workflows. If you (or anyone you know) worked on Eikon or its iterations, please reach out through this form to share your side of the story. It might just help arrest the next meltdown already in progress - LSEG Microsoft Partnership.

Prior to the VDBs, the Latin and French etymology referred to leather and purse leading to a strange chicken or egg situation we’ll discover at the end of the post.

The sources for this post are far too many to cite. Where you’d like to verify a statement, plex.it

Flanders – the county of the Flemings. Two phonetically intriguing words to describe the area and the people of modern day northern Belgium

A commercial and defensive alliance of merchant guilds and market towns on the coast of the Baltic and the North Sea. It was founded by German communities stretching eight countries, from Holland to Latvia, and lasted five centuries.

An early precursor to special economic zones that have now become a standard toolkit of economies trying to encourage trade and production.

A precursor to the risk distribution mechanism of joint stock companies that would soon emerge in neighbouring Amsterdam to fund colonial pursuits and plunder.

Still the third-highest brick tower in the world; the first two are in Germany.

CZ and Brian Armstrong are names many will recognise as the founders of Binance and Coinbase. Few can name the CEOs of NYSE, Nasdaq or Deutsche Bourse. New exchanges lean heavily on personal trust. In some cases, entirely. Famed VCs cut $100m+ checks to fraudulent SBF/FTX on blind personal trust. Oddly, once you achieve systemic trust, you can get away with worse, poorly allocating billions in investor capital. LSEG buying Refinitiv, DB buying SimCorp, Nasdaq buying Adenza. The list is long, and I digress.

This was a great read. If you haven’t already read it, Walter Mattli’s book, Darkness by Design, may be of interest to you. I worked on the book as an RA, and it also examines the benefits of centralized monopolistic exchanges (focusing on NYSE pre-algo trading). We also have a book chapter looking at patterns of change in market structure, how they fluctuate from centralization to fragmentation. But we certainly didn’t consider the possibility of one exchange engaging in armed conflict with another! https://academic.oup.com/edited-volume/35422/chapter-abstract/303179146?redirectedFrom=fulltext